-40%

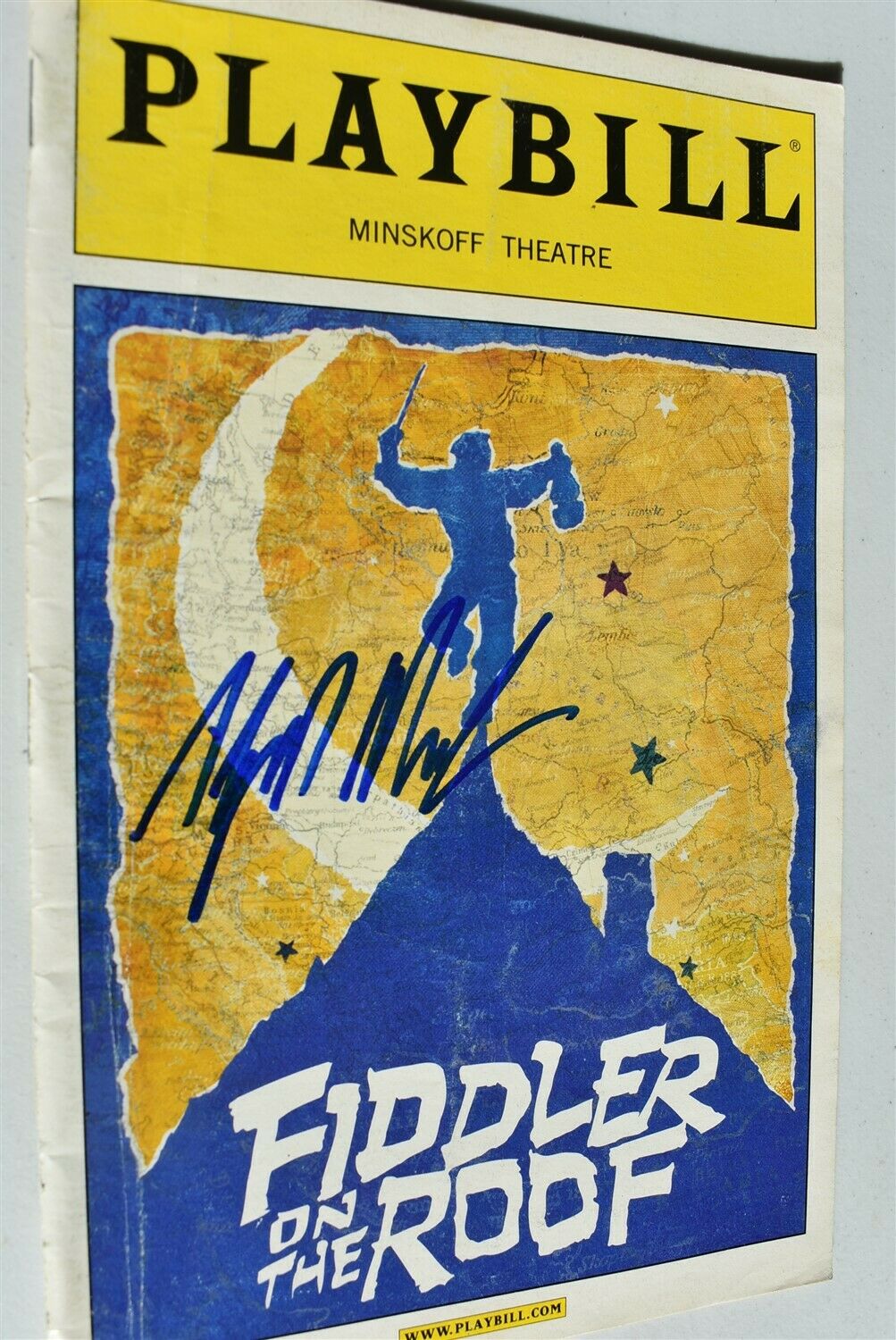

RARE Autograph Letter Signed FAMOUS Actor William LeMOYNE 1890 Uncle Tom's Cabin

$ 155.76

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

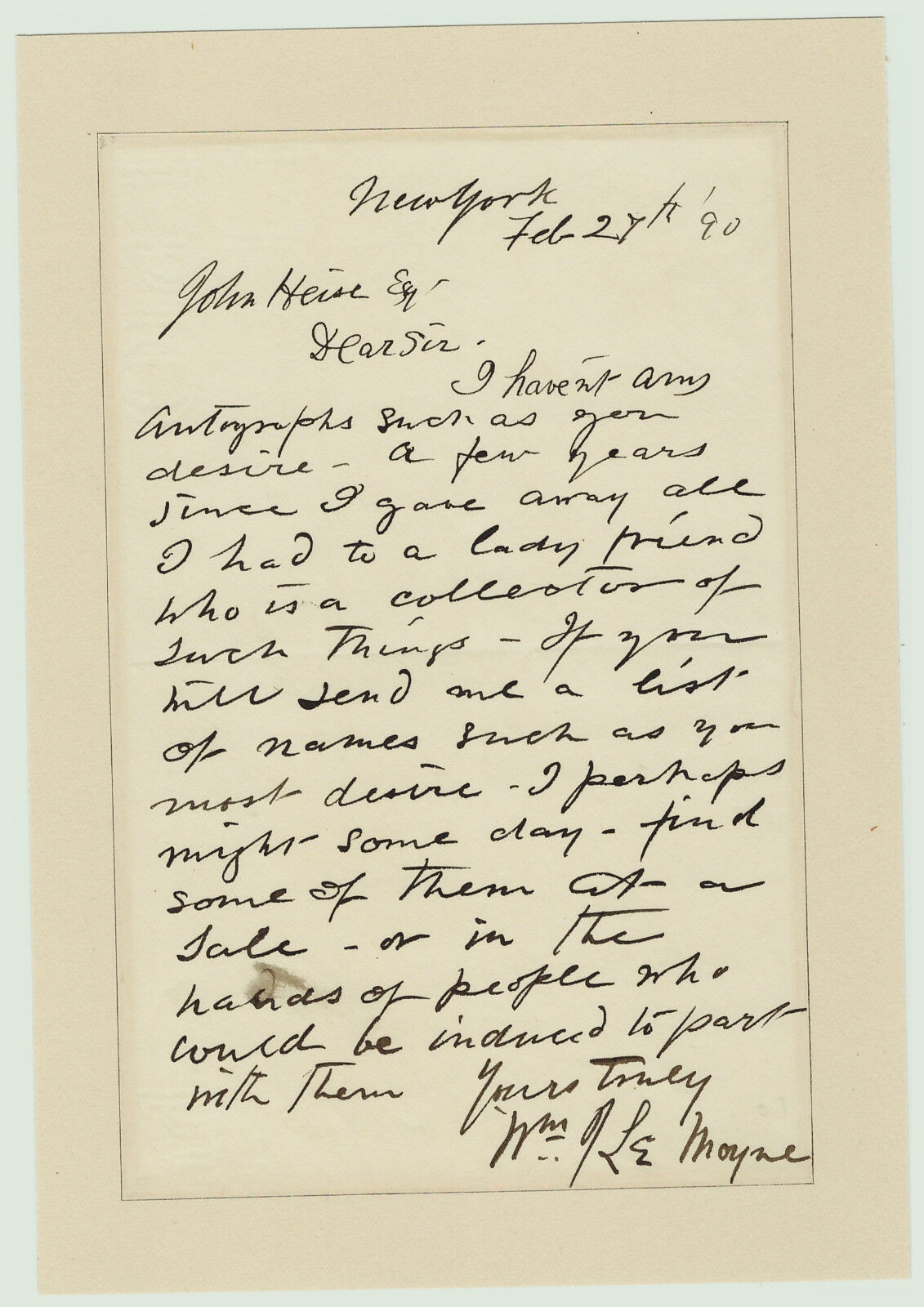

RAREAutograph Letter Signed

Famous American Actor

in 1st Stage Production of

Uncle Tom's Cabin

William J. LeMoyne

Also served in Civil War

1890

For offer, an ORIGINAL signed autograph manuscript letter.

Vintage, Old, antique, Original -

NOT

a Reproduction - Guaranteed !!

Interesting content. William J. Le Moyne(1831–1905) was an American actor who is credited with playing Deacon Perry in the first stage adaption of Harriet Beecher Stowe's anti-slavery novel, Uncle Tom's Cabin. In very good condition. Please see photos for details.

If you collect American history, Americana 19th century autograph manuscript handwriting,

letters, correspondence, entertainment, acting, dance, stage, theatre, etc., this is one you will not see again. A nice piece for your paper / ephemera collection. Perhaps some genealogy research information as well.

Combine shipping on multiple bid wins! 351

William J. Le Moyne(1831–1905) was an American actor who is credited with playing Deacon Perry in the first stage adaption of Harriet Beecher Stowe's anti-slavery novel, Uncle Tom's Cabin.

Early career

William J. Le Moyne (sometimes spelled Lemoyne or LeMoyne) was born on April 29, 1831 in Boston, Massachusetts[1][2] where he began performing in amateur theater productions at around the age of fifteen.[3] Le Moyne may have briefly supported himself as a silversmith[4] before his professional stage debut on May 10, 1852 at Portland, Maine playing an officer in The Lady of Lyons, a romantic drama by Edward Bulwer-Lytton.[5] Later that year Le Moyne joined the repertory company at Peale's Museum in Troy, New York, as a a-week 'utility man' (bit player) that was later increased to after he demonstrated an ability to play 'old man roles'. The company was largely made up of friends and family of its manager, George C. Howard and is remember for staging the first production of Uncle Tom's Cabin on September 27, 1852 at Peal's Museum.[6] The play was an immediate hit and had a run of one hundred performances, remarkable at the time for a community the size of Troy. Le Moyne's tour with Uncle Tom's Cabin the following year paved the way for his one day becoming an actor of national standing.

Military Service

At the outbreak of the American Civil War Le Moyne enlisted as a first lieutenant with Company B of the 28th Massachusetts Volunteers under the command of fellow actor Lawrence Barrett. At some point Barrett resigned and Le Moyne assumed command only to witness over half his men killed or wounded in a string of Northern defeats in South Carolina and Virginia. In September 1862, Le Moyne himself was severely wounded during the Battle of South Mountain and was unable to return to military service. He was later granted by congress a retroactive promotion to the rank of captain dating back to the point he assumed command of company B.[7]

Career

In 1863 Le Moyne returned to the stage where he remained active until the dawn of the twentieth century. He appeared in a number of plays based on the works of Charles Dickens playing such characters as Fagin, Captain Cuttle, Uriah Heep, Squeers, Plummer, Dick Swiveller and Caleb. In Shakespeare's Hamlet Le Moyne is said[who?] to have played every major male role except that of the prince himself. Over his career Le Moyne performed with companies headed by legendary actors Edwin Booth, Edwin Forrest and Charles Fletcher, and in producer Daniel Frohman's Lyceum Theatre Company.[8] Heart trouble forced Le Moyne to retire from the stage in 1901 after supporting James K. Hackett in Don Caesar's Return.

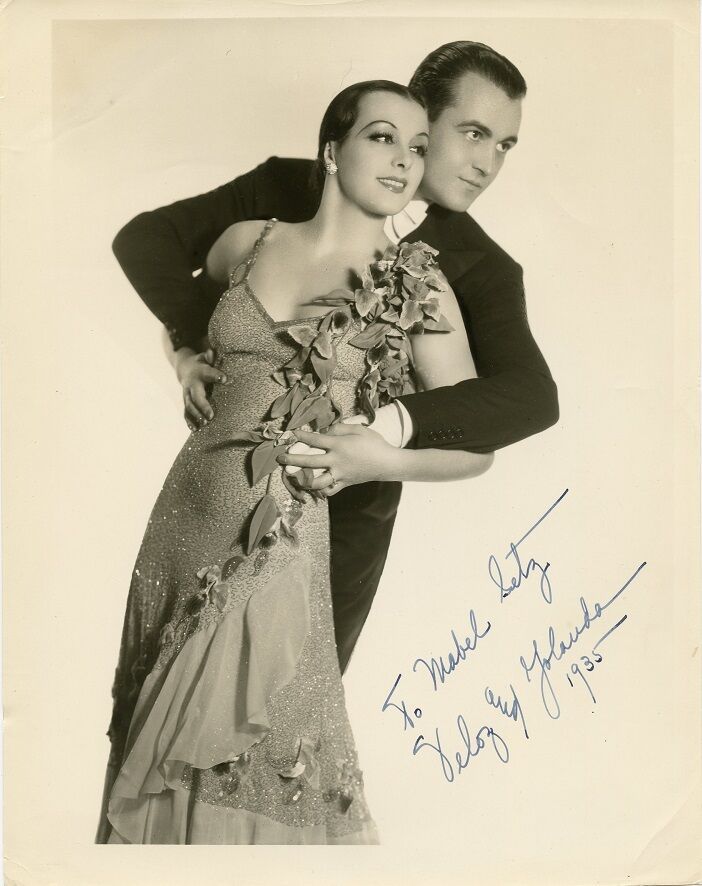

Mrs. Sarah Cowell Le Moyne (ca. 1900)

Marriage

His first marriage to actress Sarah Le Moyne ended in divorce in 1886 or 87. He married his second wife, actress Sarah Emma Cowell, in June 1888 [9] and remained with her until the end of his life. Sarah, who was an accomplished actress and reader at the time of their marriage, went on to have a successful Broadway career under her married name.

William J. Le Moyne - Self Portrait in Watercolor (ca. 1880)- Courtesy Mary Chitty - Life and Times of Actress E.J. Phillips

Hobbies

Le Moyne was an eclectic collector whose house was adorned with paintings of Chinese actors, old plaques, a variety of smoking pipes, an idol from a Chinese temple, antique children's shoes, artifacts from several ancient American and Asian cultures and works by contemporary American artists. He had also gathered a large assortment of horseshoes, his favorite being one he found in New York City on Thirteenth Street one Friday with seven nails still attached. Le Moyne's most valuable collection would come from a lifelong passion for obtaining old and rare books. Offstage Le Moyne was also known as a painter in the medium of water colors.[10]

Death

William J. Lemoyne died after several years of declining health on November 6, 1905, at a friend's residence in Inwood-on-the-Hudson[11] (now Inwood), a neighborhood on the northern shore of Manhattan Island.

Plays

1852 Lady of Lyons First Officer

1852 Ingomar Friar Lawrence, Sir Oliver Surface, Eugene Delorme and Polydore

1852 Uncle Tom's Cabin Deacon Perry

1891 Old Heads and Young Hearts Jesse Rule

1887 The Wife (play) Major Homer Q. Putnam

1872 The Provoked Husband John Moody

1889 London Assurance Sir Harcourt Courtly

1872 Article 47 Old Simon

1872 Road to Ruin Silky

1872 The Inconstant Caius

1882 Manhood (play) Peter Sharpley

1885 Saints and Sinners Deacon Samuel Hoggard

1883 The Rajah Joseph Jeckyll

1883 Sealed Instructions Mons Cervais

1889 The Charity Ball Ex-Judge Peter Gurney Knox

1888 Sweet Lavender Barrister Dick Phenyl

1891 Lady Bountiful Rederick Heron

1895 The Case of Rebellious Susan Admiral Darby

1895 The Private Secretary Lord Blayver

1886 Jim, the Penman Baron Hartfeldt

1896 The Benefit of the Doubt Fletcher Portwood

1872 Divorce Detective Burritt

1892 Squire Kate Gaffer Kingsley

1886 Our Society Reginald Rae

1898 Catherine M. Vallon

1900 The Choir Invisible Rev. James Moore

1900 Naughty Anthony Adam Budd

1898 The Moth and the Flame Mr. Dawson

1897 The Coat of many Colors Florian Walboys

1898 Tess of the D'Urbervilles John Durbeyfeld

1897 Roaring Dick and Co. Mr. Pontifax

1900 Don Caesar's Return Marquis of Gonzalo

Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly,[1][2] is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in 1852, the novel "helped lay the groundwork for the Civil War", according to Will Kaufman.[3]

Stowe, a Connecticut-born teacher at the Hartford Female Seminary and an active abolitionist, featured the character of Uncle Tom, a long-suffering black slave around whom the stories of other characters revolve. The sentimental novel depicts the reality of slavery while also asserting that Christian love can overcome something as destructive as enslavement of fellow human beings.[4][5][6]

Uncle Tom's Cabin was the best-selling novel of the 19th century and the second best-selling book of that century, following the Bible.[7][8] It is credited with helping fuel the abolitionist cause in the 1850s.[9] In the first year after it was published, 300,000 copies of the book were sold in the United States; one million copies in Great Britain.[10] In 1855, three years after it was published, it was called "the most popular novel of our day."[11] The impact attributed to the book is great, reinforced by a story that when Abraham Lincoln met Stowe at the start of the Civil War, Lincoln declared, "So this is the little lady who started this great war."[12] The quote is apocryphal; it did not appear in print until 1896, and it has been argued that "The long-term durability of Lincoln's greeting as an anecdote in literary studies and Stowe scholarship can perhaps be explained in part by the desire among many contemporary intellectuals ... to affirm the role of literature as an agent of social change."[13]

The book and the plays it inspired helped popularize a number of stereotypes about black people.[14] These include the affectionate, dark-skinned "mammy"; the "pickaninny" stereotype of black children; and the "Uncle Tom", or dutiful, long-suffering servant faithful to his white master or mistress. In recent years, the negative associations with Uncle Tom's Cabin have, to an extent, overshadowed the historical impact of the book as a "vital antislavery tool."

Tom show is a general term for any play or musical based (often only loosely) on the 1852 novel Uncle Tom's Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe. The novel attempts to depict the harsh reality of slavery. Due to the weak copyright laws at the time, a number of unauthorized plays based on the novel were staged for decades, many of them mocking the novel's strong characters and social message, and leading to the pejorative term "Uncle Tom".

Even though Uncle Tom's Cabin was the best-selling novel of the 19th century, far more Americans of that time saw the story in a stage play or musical than read the book.[1] Some of these shows were essentially minstrel shows that utilized caricatures and stereotypes of black people, and thus inverting the intent of the novel. "Tom shows" were popular in the United States from the 1850s through the early 1900s.

The shows

Stage plays based on Uncle Tom's Cabin—"Tom shows"—began to appear while the story itself was still being serialized. These plays varied tremendously in their politics—some faithfully reflected Stowe's sentimentalized antislavery politics, while others were more moderate, or even pro-slavery.[2] A number of the productions also featured songs by Stephen Foster, including "My Old Kentucky Home," "Old Folks at Home," and "Massa's in the Cold Ground."[1]

Stowe herself never authorized dramatization of her work, because of her puritanical distrust of drama (although she did eventually go to see George Aiken's version, and, according to Francis Underwood, was "delighted" by Caroline Howard's portrayal of Topsy).[3] Asa Hutchinson of the Hutchinson Family Singers, whose antislavery politics closely matched those of Stowe tried and failed to get her permission to stage an official version; her refusal left the field clear for any number of adaptations, some launched for (various) political reasons and others as simply commercial theatrical ventures.

Eric Lott, in his book Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class, estimates that at least three million people saw these plays, as many as the novel's worldwide sales. Some of these shows were basically just blackface minstrel shows only loosely based on the novel, and their grossly exaggerated caricatures of black people further perpetuated, for purposes of mockery, some of the stereotypes that Stowe had used more innocently.[3]

Productions

Eliza crossing the ice, in an 1881 theater poster for a production by the Jarrett & London Company and Slavin's Original American Troupe.

All "Tom shows" appear to have incorporated elements of melodrama and blackface minstrelsy.

The first serious attempt at anything like a faithful stage adaptation was a one-hour play by C.W. Taylor at Purdy's National Theater (New York City); it ran for about ten performances in August–September 1852 sharing a bill with a blackface burlesque featuring T.D. Rice. Rice, famous in the 1830s for his comic and clearly racist blackface character Jim Crow, later became the most celebrated actor to play the title role of Tom; when Rice opened in H.E. Stevens play of Uncle Tom's Cabin in January 1854 at New York's Bowery Theatre, the Spirit of the Times' reviewer described him as "decidedly the best personator of negro character who has appeared in any drama."

The best-known "Tom Shows" were those of George Aiken and H.J. Conway.[4]

Aiken's original Uncle Tom's Cabin focused almost entirely on Little Eva (played by child star Cordelia Howard); a sequel, The Death of Uncle Tom, or the Religion of the Lonely told Tom's own story. The two were ultimately combined in an unprecedented evening-long six-act play. According to Lott, it is generally faithful to Stowe's novel, although it plays down the trickster characters of Sam and Andy and variously adds or expands the roles of some farcical white characters instead. It also focuses heavily on George Harris; the New York Times reported that his defiant speech received "great cheers" from an audience of Bowery b'hoys and g'hals. Even this most sympathetic of "Tom shows" clearly borrowed heavily from minstrelsy: not only were the slave roles all played by white actors in blackface, but Stephen Foster's "Old Folks at Home" was played in the scene where Tom is sold down the river. After a long and successful run beginning November 15, 1852 in Troy, New York, the play opened in New York City July 18, 1853, where its success was even greater.

Conway's production opened in Boston the same day Aiken's opened in Troy; P.T. Barnum brought it to his American Museum in New York November 7, 1853. Its politics were much more moderate. Sam and Andy become, in Lott's words, "buffoons". Criticism of slavery was placed largely in the mouth of a newly introduced Yankee character, a reporter named Penetrate Partyside. St. Clare's role was expanded, and turned into more of a pro-slavery advocate, articulating the politics of a John C. Calhoun. Legree rigs the auction that gets him ownership of Tom (as against Stowe's and Aiken's portrayal of oppression as the normal mode of slavery, not an abuse of the system by a cheater). Beyond this, Conway gave his play a happy ending, with Tom and various other slaves freed.

Showmen felt that Stowe's novel had a flaw in that there was no clearly defined comic character, so there was no role for a comedian, and consequently little relief from the tragedy. Eventually it was found that the minor character of Marks the Lawyer could be played as a broad caricature for laughs, dressing him in foppish clothes, often equipped with a dainty umbrella. Some productions even had him make an entrance mounted astride a large pig.

Diluting the message of Stowe's book

"Tom shows" were so popular that there were even pro-slavery versions. Among the most popular was Uncle Tom's Cabin as It Is: The Southern Uncle Tom, produced in 1852 at the Baltimore Museum.[5] Lott mentions numerous "offshoots, parodies, thefts, and rebuttals" including a full-scale play by Christy's Minstrels and a parody by Conway himself called Uncle Pat's Cabin, and records that the story in its many variants "dominated northern popular culture… for several years".

According to Eric Lott, even those "Tom shows" which stayed relatively close to Stowe's novel played down the feminist aspects of the book and Stowe's criticisms of capitalism, and turned her anti-slavery politics into anti-Southern sectionalism.[6] Francis Underwood, a contemporary, wrote that Aiken's play had also lost the "lightness and gayety" of Stowe's book. Nonetheless, Lott argues, the plays increased sympathy for the slaves among the Northern white working class (which had been somewhat alienated from the abolitionist movement by its perceived elitist backing).

Influence

The influence of the "Tom shows" can be found in a number of plays from the 1850s: most obviously, C.W. Taylor's dramatization of Stowe's Dred, but also J.T. Trowbridge's abolitionist play Neighbor Jackwood, Dion Boucicault's The Octoroon, and a play called The Insurrection, based on John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry.

Still from Edwin S. Porter's 1903 version of Uncle Tom's Cabin, which was one of the first "full length" movies. The still shows Eliza telling Uncle Tom that she has been sold and that she is running away to save her child.

The influence of the "Tom shows" also carried over into the silent film era (with Uncle Tom's Cabin being the most-filmed story of that time period).[7] This was due to the continuing popularity of both the book and "Tom shows," meaning audiences were already familiar with the characters and the plot, making it easier for the film to be understood without spoken words.[7]

Several of the early film versions of Uncle Tom's Cabin were essentially filmed versions of "Tom shows." These included:

A 1903 version of Uncle Tom's Cabin, which was one of the earliest "full-length" movies (although "full-length" at that time meant between 10 and 14 minutes).[8] This film, directed by Edwin S. Porter, used white actors in blackface in the major roles and black performers only as extras. This version was similar to many of the "Tom Shows" of earlier decades and featured a large number of black stereotypes (such as having the slaves dance in almost any context, including at a slave auction).[8]

Another film version from 1903 was directed by Siegmund Lubin and starred Lubin as Simon Legree. While no copies of Lubin's film still exist, according to accounts the movie was similar to Porter's version and reused the sets and costumes from a "Tom Show."[9]

As cinema replaced vaudeville and other types of live variety entertainment, "Tom shows" slowly disappeared. J.C. Furnas, in his book Goodbye to Uncle Tom, stated that he had seen a production in the 1920s in Ohio; the last touring group specializing in "Tomming" he could locate was apparently operating as late as the 1950s.